|

This document contains the World War II

memories of Gardner L. Friedlander.

According to the July 1990

"Smithsonian" magazine, radar had been "in the

works" in Germany as early as 1933. Not long after that it

started being developed in England, France, Italy, Russia, and

the United States. Only England, however, really pushed radar

and its practical use. By the time the Nazis were ready to start

the blitz of England in July 1940, England had 29 radar stations

making an invisible curtain along its southern and eastern

coasts.

France fell to the Nazi blitzkrieg in June 1940,

the same week I graduated from Dartmouth. For two college summer

vacations I had worked in Chicago as a management trainee and

after graduating I was working there full time. A very low draft

number led to my enlisting in the army "one step ahead of

the sheriff" and let me join my brother and friends in the

32nd Division (National Guard). The 32nd had been called to

active service and was training at Camp Livingston, Louisiana.

It wasn't easy to quit

the job to start an unknown life, but after all, it was to be

for only one year(!). I joined about 100 other young men at the

Whitefish Bay armory for a final physical (which everyone prayed

he'd fail). We bussed to Camp Grant near Rockford, Illinois.

This was my home for a few weeks. I was sort of on permanent KP.

I never knew there were so many potatoes to peel, or so many

dirty pots, pans, and garbage pails to clean. Eventually, a

contingent of enlistees and draftees was sent to join the 32nd

Division, and I was on my way to "tent city in the

Louisiana swamp" as it was not too affectionately known.

I took basic training with the 127th Infantry. I was then

transferred to the 121st Field Artillery, where I served as a

radio operator in an antitank company, and was with brother Ted

during the summer maneuvers in Louisiana and Texas.

My part of the war games ended when I

was taken to the Camp Livingston hospital with a

severe case of poison ivy caught by sleeping in a

poison ivy patch. This was complicated by my being

placed in the measles ward where I caught that disease

as well as getting an infection in my left leg, which

the ward doctor said was to be amputated. Exciting!

Brother Ted got in touch with Dad, who pulled enough

strings to have the major medical powers at Camp

Livingston visit me at bedside. That ended talk of

amputation, and it wasn't long before I was 100% and

back on duty.

|

(Click for transcript.)

|

Maneuvers were

over, and after a month or so I got two weeks of

leave: Milwaukee!. On my return to camp in late

October 1941 I found that I had been

"battle field" promoted to 2nd

lieutenant, Signal Corps, 0-430118. I was posted

to Fort Monmouth, N.J., for a quick introduction

to the then new and very secret RADAR. It would

be the center of my life until 1945

|

Radar and its tactical use had been developed in

England by Sir Watson Watt, and was credited

with being the decisive factor in saving England

during the blitzes. Its usefulness was such a secret

that we were forbidden to mention it away from

wherever we were using it; forbidden to keep a diary

or to carry a camera; and when leaving school, were

given chemistry or astronomy books to carry to cloak

what we were studying.

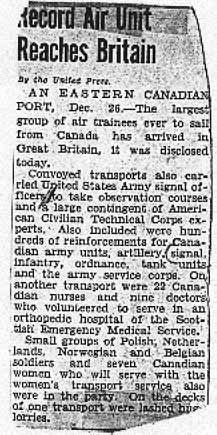

| Fifty

of us with physics or electrical

engineering degrees were assembled at Ft.

Monmouth to be sent to England for

intensive radar training. We were supposed

to embark December 1st, 1941, but actually

didn't sail (from Halifax, Nova Scotia)

until December 10th (three days after

Pearl Harbor and the United States entry

into the war). We joined a British troop

ship convoy with some 25,000 United

Kingdom soldiers and other personnel, most

of whom were RAF fliers, gunners, and

mechanics who had been trained in Canada

and the USA. We had tremendous naval

protection. Our troop ship, perhaps one of

a dozen, was HMS "Potsdam." |

|

Life on board ship was not like pleasure

cruising. We were eight officers to a cabin

which in peace time would have been for two

passengers, with bunks four high. We were at

that in much more comfort than the enlisted

personnel sleeping four or six high in

hammocks. Food was O.K., served to all of us

the same, in mess kits. We would squat down

someplace to eat...on deck in good weather.

|

(Click for transcript.)

|

Life on board ship was not like pleasure

cruising. We were eight officers to a cabin which in

peace time would have been for two passengers, with

bunks four high. We were at that in much more

comfort than the enlisted personnel sleeping four or

six high in hammocks. Food was O.K., served to all

of us the same, in mess kits. We would squat down

someplace to eat...on deck in good weather.

|

For more information on these memoirs and

accompanying photos, please click on to Mr.

Friedlander's web

site.

| Editor's note: |

Gard originally wrote these memoirs in

1990 for his children and grandchildren; they

do not contain descriptions of the violence of the

war. The web version of Gard's memoirs was created

in April, 2000. |

|